The National Socialist Ideology

Propaganda

propaganda poster.

The Germans tried to influence the Dutch population with an overwhelming amount of propaganda material. Cinema newsreels, pamphlets, brochures and colour posters were intended to drum into everyone's head the unstoppable victory of National Socialism. Dormant aversion to the Jews was stirred up and the fear of communism was fed.

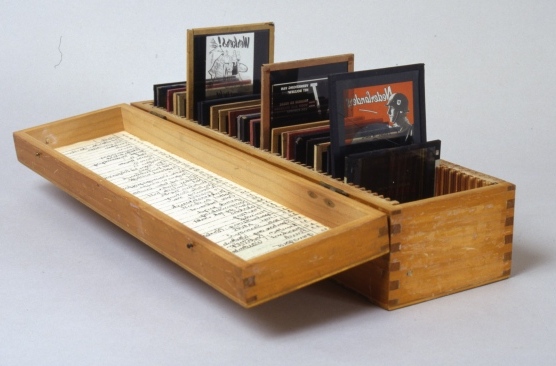

Propaganda slides

A box of propaganda slides as shown in the cinemas between the films and newsreels. Dutch cinemas are used for German propaganda from February 1941.

V=Victory

Allied aeroplanes dropped pamphlets that challenged the German propaganda. The letter V became a symbol for Victory. In the summer of 1941, the Germans adopted the V in their own campaign: 'V = Victory, because Germany is victorious on all fronts'. In a counter move, the Dutch vandalised the posters. The V became W, for Wilhelmina, or V for Verliest (loses) or Verzuipt (drowns).

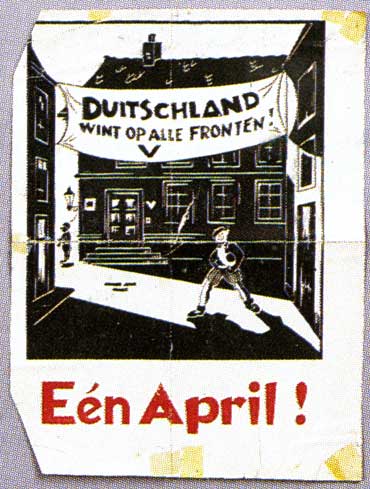

April Fools Day

will win the war.

A poster made by Joop Leijen - a Amsterdam resident - in reaction to the German V-campaign in 1941. Joop was asked to draw the poster by the father of his friend Krijn Dolman.

Krijn: ‘When the Germans lost, the slogan became somewhat ironic. My father thought it was time the Amsterdam people showed they did not much appreciate the presence of the Krauts.’ The drawing was made into a linocut. Joop Leijen: ‘We printed 200 posters. A mammoth task. They were put up at night on April 1st 1944.’

Schools

The occupiers wanted to use the schools to give children a National Socialist upbringing, but they knew this plan would be met with a lot of resistance. People in the Netherlands attached great value to their own educational system in which the different religious groups had separate schools.

The German measures were limited. NSB members were given preference in the appointment of teachers. Some school books were banned or changed. The number of required hours of German study was increased.

Anti-German attitude

The attitude among pupils and teachers was generally fiercely anti-German. There were plenty of Nazi jokes and songs going around. NSB children and NSB teachers were harassed. As the occupation continued, the disruption of society meant an increase in truancy. During the last winter of the war many schools were forced to close because of the lack of fuel.

Even before the war, Dutch churches had condemned National Socialism. During the occupation they repeatedly sent letters to Seyss-Inquart to protest the persecution of the Jews and other German measures. Church protests were also read aloud from the pulpit. In addition, many clergymen urged their congregations to help those in hiding.

Hendrica de Visser, housewife from Amsterdam:

'In church you prayed together that you might be spared in these dark times. You and all the other people in need. For a while it gave you the feeling that you were part of a community. That gave me the strength to go on. I also prayed every night at home for the people, for the queen, and yes, also for the Jewish people who were suffering so terribly. Many people became church-goers particularly during the war.'

'In church you prayed together that you might be spared in these dark times. You and all the other people in need. For a while it gave you the feeling that you were part of a community. That gave me the strength to go on. I also prayed every night at home for the people, for the queen, and yes, also for the Jewish people who were suffering so terribly. Many people became church-goers particularly during the war.'

Hilde Dekker was a courier in Groningen:

'It gave me courage when a church minister openly called on people to resist. I noticed it in my work with the resistance, too. If a minister somewhere acted according to his principles, it was possible to hide many more people there. In the southern part of the Netherlands, where almost everyone was Catholic, this tendency was even stronger. If the priest said that the people in hiding had to be helped, virtually everyone lent a hand.'

'It gave me courage when a church minister openly called on people to resist. I noticed it in my work with the resistance, too. If a minister somewhere acted according to his principles, it was possible to hide many more people there. In the southern part of the Netherlands, where almost everyone was Catholic, this tendency was even stronger. If the priest said that the people in hiding had to be helped, virtually everyone lent a hand.'

Protestant resistance

At the beginning of the occupation, many Protestant Christians wondered whether resistance work was morally permissible. In June 1942, a delegation went to consult with the Swiss theologian Karl Barth, a man of great authority. His advice was clear: participating in resistance work is not only justified, it is even compulsory. This advice was publicised in illegal pamphlets.

The churches wielded so much authority in the Netherlands that the occupiers behaved with great caution. But the influence of the churches was indirectly reduced when so many social institutions came under National Socialist leadership.